ROOTS: Against the Backdrop of #MeToo, Ireland Reckons with its History of Structural Violence Against Women

Irish news rarely makes its way to America unless you seek it out. So, you would be forgiven for assuming that #MeToo looked the same in Ireland as it did everywhere else. And in a lot of ways, to my American eyes, it did. But lately in Ireland, something much rarer and more powerful has been going on—something that could only happen in Ireland, but that other countries should undoubtedly notice.

The past several years have been some of the most tumultuous in the history of modern Ireland. A series of scandals and revelations have forced the country to confront some of the ugliest parts of its past—and to decide how it wants the future to look.

For centuries, Ireland was a deeply Catholic country. The Catholic Church has wielded enormous influence in the country for decades—ever since the Irish Free State declared that it would occupy “a privileged place” in Irish public life. But now, that may be changing.

Beginning in the late 1990s, and continuing to the present, Ireland has been rocked by a series of scandals involving the Catholic Church. Those who had been abused—physically and sexually—by members of the Church hierarchy as children have been coming forward to demand answers, accountability, and change.

Up until now, the authority of religious figures was rarely questioned. But this would come to an end. As more and more victims came forward, it became clear that the abuse of children around the world had been facilitated by a church hierarchy that used its social clout to protect abusers and silence victims. Faced with this ugly revelation, many in Ireland would come to question their relationship with the Church. And this was only the beginning.

In 2012, an essay published by amateur historian Catherine Corless would again force Ireland to confront a dark piece of its history. Corless had been researching Ireland’s mother and baby homes, Church-run institutions that cared for unmarried pregnant women and kept their children (sometimes adopting them out, as seen in the movie Philomena)—having children out of wedlock an unspeakable shame in Ireland. Corless had found that she could not find burial records for a large number of children who died in one of these institutions at Tuam—but she did find what she thought was an unmarked mass grave at the back of the property. More research would reveal that she was correct, and that a total of 796 bodies were buried on the property.

Nor was this a complete shock: as early as the 1930s, the Irish government debated whether to look into the fact that “home babies,” as they were called, were much less likely to survive childhood than their peers. Nevertheless, nothing changed.

Nothing changed until Corless shared her work with The Irish Mirror in 2014. The story spread like wildfire. It eventually forced the embarrassed Irish government to create a task force to examine exactly what happened—and to how many women and children.

As this investigation unfurled, it revealed links to another group of institutions that was quietly notorious for its mistreatment of women: the Magdalene laundries.

Ireland’s Magdalene laundries saw thousands of “fallen women”—sex workers, unwed mothers, rape victims, and others—as well as orphans, street children, and children otherwise removed from their homes, confined in the laundries and forced to work.

Just this year, the Irish government has hosted a conference where women who had been victims of the laundries were able to express their grievances, hold their government to account, and even reconnect with women they met during their harrowing experiences.

Many of these women had since left Ireland—the social stigma of having been in a laundry was too great a burden to bear. Many émigrées struggled to get passports to even come, as they were never given access to their vital documents—if they ever had them at all. Huge numbers have begun looking for parents, siblings, and children from whom they were forcibly separated.

This has forced the country to confront the things it knew about, but never before talked about. It has also brought to light things that many did not even know about: women being coerced to give their children up for adoption, often to Americans, as well as the use of children in the custody of these institutions (and even their cadavers) for medical research.

Lest you think that this is entirely a matter of history, Ireland has also recently been confronting scandals of a different, but not unrelated variety. The story of Savita made headlines around the world. Having presented to the emergency room in the early stages of a miscarriage, Savita Halappanavar requested an abortion to end her obviously nonviable pregnancy. However, abortion for reasons other than saving the mother’s life is illegal in Ireland, punishable by a 14-year prison sentence, so she was refused. She eventually developed sepsis as a result, and died at 31 years of age. Her death sparked protests across Ireland, calling for a change in the country’s draconian abortion laws.

Women’s health has caused other kinds of contention in Ireland, as well. In April of this year, news broke that hundreds of cervical cancer screenings had come back with false negatives. This has left at least 208 women with advanced-stage cervical cancer that could likely have been treated if it had been caught early. 17 more women have died. The Irish government established a hotline to field questions from women concerned about their own test results, and it received thousands of calls in its first few days. The government continues to search for answers and try to work out a solution.

These scandals have left the Irish people confused, angry, and trying to place blame. Some blame the Church, once revered, which has now become a target of resentment for those angry that these atrocities were carried out in their name. But then, if the Church is to blame, surely so must the Irish state be. The two have been closely linked since Ireland won its independence.

These scandals reflect a society where patriarchy is deeply entrenched; a society that categorically does not value women. While some would argue that this is purely a result of the deeply-entrenched religious structure, that does not explain everything. Patriarchy exists independently of religion, although the two certainly enable each other. The cervical cancer scandal unfolded only in the past few years, while the Church’s influence in Ireland was already declining. If women were always valued in Irish society (or any society), an institution that would have them relegated to the shadows would never have been allowed to dominate the public sphere. It is precisely because women were historically undervalued that their mistreatment was allowed to happen and tolerated for so long.

Like many countries, cultural violence against women has long existed. This cultural violence is comprised of the negative attitudes towards women that convinced so many that their mistreatment was acceptable. This cultural violence then translated into structural violence: policies facilitating this mistreatment that represented the patriarchal system essentially codified into law.

It is important to note that these dynamics are not unique to Ireland―far from it. Many other countries share similar characteristics, and have undoubtedly seen similar things happen even if they have not been talked about. Patriarchy is deeply entrenched all over the world, so in that aspect Ireland is by no means an outlier.

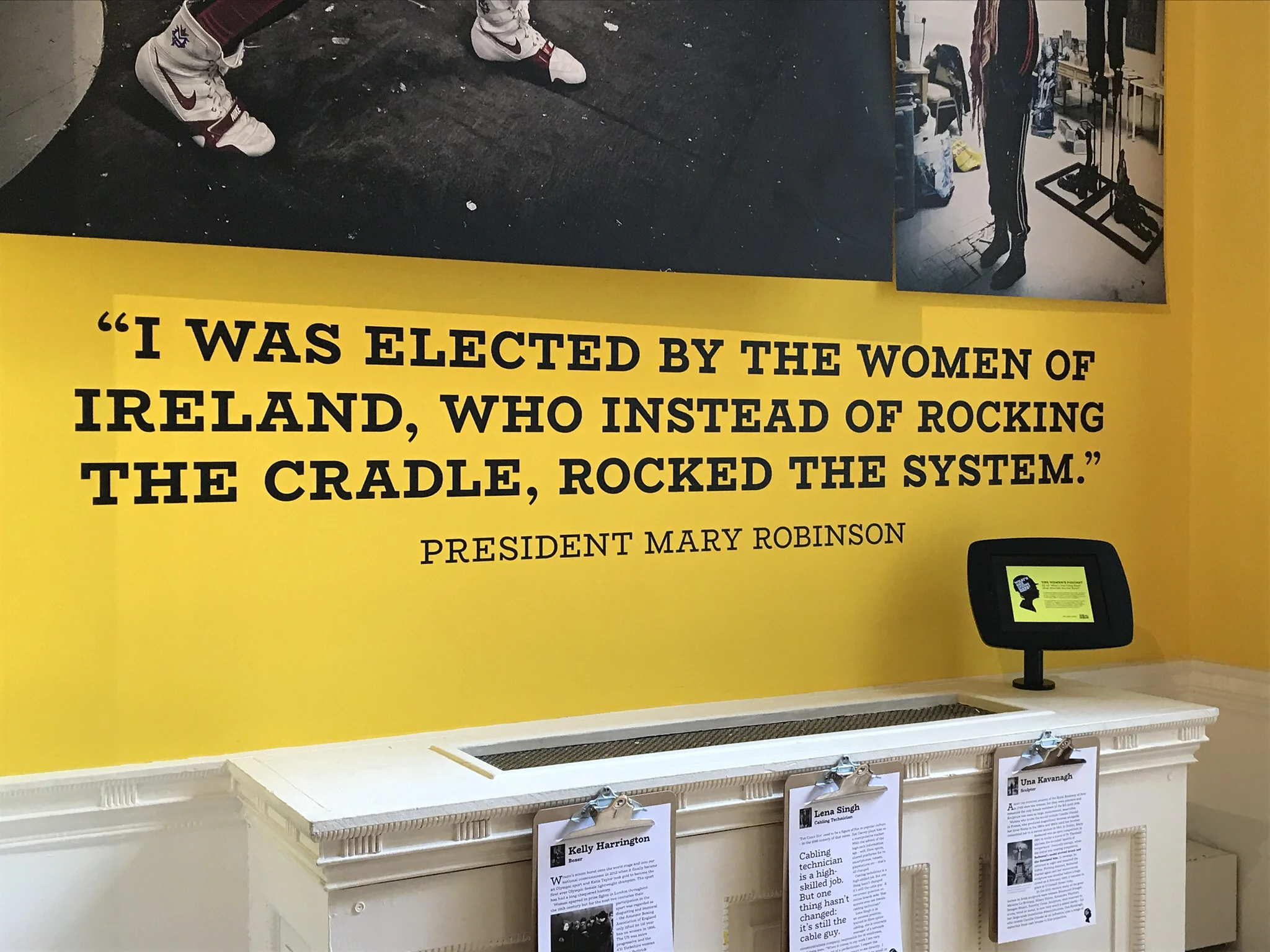

But Ireland is unique because it is moving forward. The country has become massively more progressive with regards to social issues, legalizing same-sex marriage in 2015 (becoming the first country to do so by popular vote) and voting just this year (by a huge margin, despite extensive efforts by American faith organizations to mobilize voters to reject the initiative) to begin constitutional reforms that will decriminalize abortion.

These changes may come as a shock initially, but in light of these scandals, they are not surprising—although they are most certainly encouraging and welcome. Indeed, this social change in Ireland can be read as a backlash against decades—centuries—of misogyny that the country has now been forced to confront. In this day and age, the kinds of revelations that have been made in Ireland are seen as a national embarrassment—and so they should be.

All aspects of Irish society have been touched by the events of recent years. In Ireland, it is difficult to not be aware of them. But thankfully, this has resulted in a nation consciously reckoning with the ways it has wronged its women—and vowing to do better. People are not just recognizing the specific cases of women being categorically wronged, they are engaging with the societal dynamics that made this possible and challenging their own perspectives.

These referenda reflect changing sexual morés in Ireland, true, which is important because patriarchy often functions by dominating popular perceptions about sexuality. In Ireland, notions of virginity and sexuality have long influenced the way people think about women and femininity—but apparently, not anymore. They are also reflective, however, of a fundamental change in the way the country views its women. Ireland has chosen to make this a learning experience, and work to create a country where this does not happen again. When women are no longer shamed and commodified by these sexual attitudes, they are instead truly valued members of society—and everyone is better for it.

Further Reads:

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/06/world/europe/magdalene-laundry-reunion-ireland.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catholic_Church_sexual_abuse_scandal_in_Ireland

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/10/28/world/europe/tuam-ireland-babies-children.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/30/world/europe/ireland-cervical-cancer-screening-scandal.html